Alex Katz as gateway drug

Finding those who capture the human spirit by starting with America's celebrated portraitist

My painting students all love Alex Katz. They love his iconic, breezy style of painting. They admire his seeming devotion to his wife, Ada. Then there is his palette, rich, confident, not quite what we expect but nothing too wild, either. He is a cool painter who knows when to quit when it comes to how many lines or brushstrokes or shades a painting needs. He doesn’t feel compelled to capture every leaf on a tree or wrinkle on a face. Less is more is an attractive painting style when you are just learning to paint and every decision is difficult.

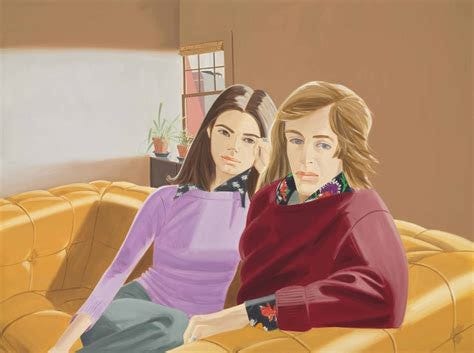

Alex Katz’s Purple Wind (1995)

And it doesn’t hurt that his art is accessible.

I don’t mean to be condescending to the artist or the people who love him. Accessibility means that he does a good job being simple and being simple is hard to do. Limiting a painting to a black hat, yellow background and a long neck is not easy to do when painting is often a celebration of more-is-more.

That accessibility makes Katz a great gateway drug for new painters to find other painters to learn from. When you are just beginning to make paintings, looking for role models to steal from is a big part of the process.

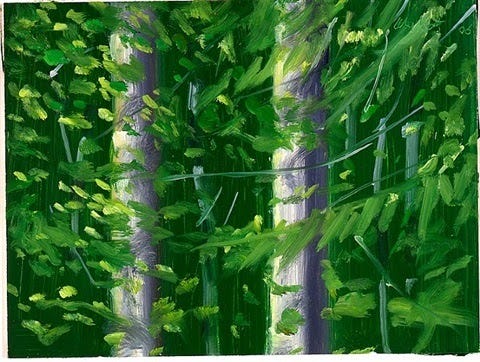

Say that a new painter falls in love with these tree paintings by Katz.

Alex Katz, Winter Landscape 1993, oil on canvas

Alex Katz’s Two Trees 1

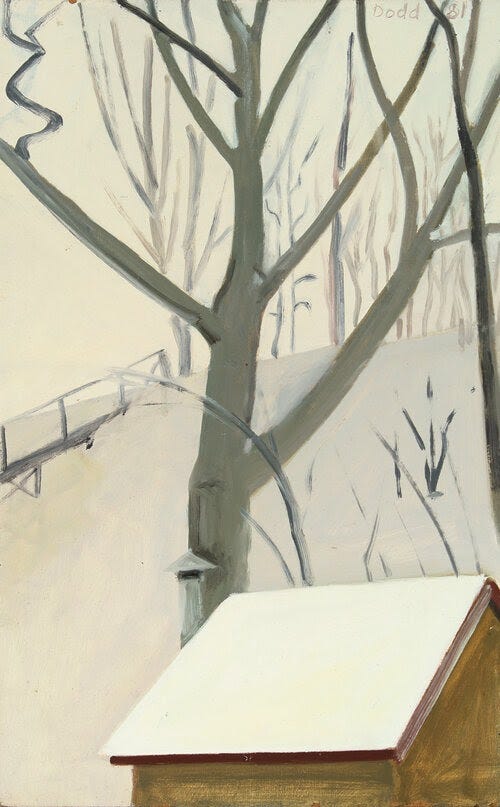

The next obvious artist for that Katz lover to explore is Lois Dodd. A contemporary painter who repeatedly uses the same motifs and subject matter, including New England forests, often paints what she sees outside her New England window. If the new painters come for the trees they might stay for the quiet mood of her world, the frozen brook, the clothes on the clothesline and see an opportunity to capture the quiet moments in their own world.

Lois Dodd, Roof With Snow, Cushing

1981, oil on Masonite, 15 7/8 x 10 inches

Lois Dodd, Winter Landscape from White House..., 1976

Katz perfected the loner in the solid field of color. I have always had a lot of questions about why he is depicting all the ladies and so few men, but let’s just leave that question out of this for a minute. He turns the canvas into a stage with the figure facing forward, confronting the viewer and capturing the way we all carry so many hints at our personality in the way we stand, lean or clasp our arms, not to mention the clothes we put on in the morning. As Katz said, despite the fact that he’s done a ton of nudes, “I like clothing, I like the way people wear clothing. It gives the picture some energy." But to me, his portraits don’t have energy, they are like a Greek kouros carved out of marble, his figures seem trapped in time.

Black Dress, 2015

Alex Katz Ada (Oval) 1959

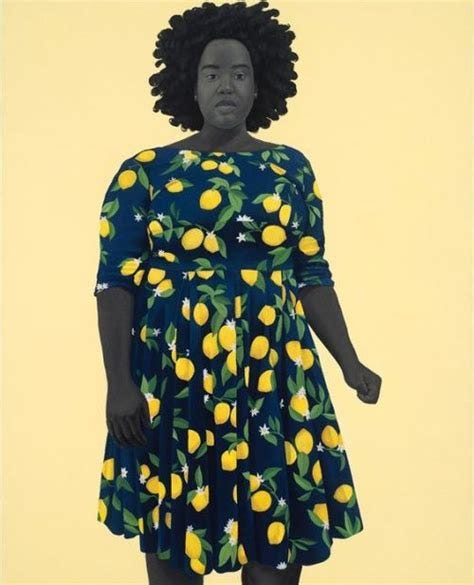

Amy Sherald has taken the solid background behind the individual and made it modern, and potentially less misogynist. Her figures are not such bugs in amber, as Katz’s are. Sherald, who shot to global fame after completing the official portrait of Michelle Obama, makes big paintings with people who seem about ready to make a move, and thanks to her compelling color combinations, they seem to almost levitate.

And while Katz’s stories get repetitive with the same people, the same patrician fashion, the same stance, Sherald makes new painters consider the specificity of their own world and the people in it and see where they can reflect that in portraits. Sherald is also a lesson in trying new things. She doesn’t land on a skin tone, she paints her people in grisaille, which to me makes her subjects feel a bit like the gold icons you find in a Greek Orthodox church. She reimagined the American portrait, as Peter Schjeldahl said in The New Yorker, her paintings are “resetting the mainstream of Western art.

SHE ALWAYS BELIEVED THE GOOD ABOUT THOSE SHE LOVED

2018, 54 x 43 inches, Oil on Canvas

TRY ON DREAMS UNTIL I FIND THE ONE THAT FITS ME. THEY ALL FIT ME.

2017, 54 x 43 inches, Oil on Canvas

A CLEAR UNSPOKEN GRANTED MAGIC

2017, 54 x 43 inches, Oil on Canvas

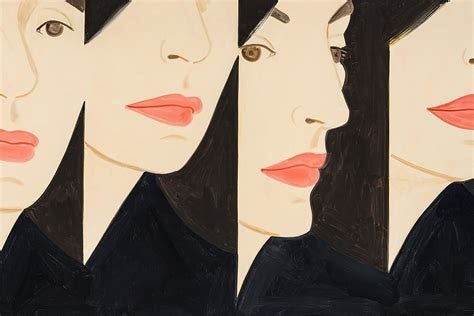

Katz often does his models in multiples, and those women in repeat are usually Ada. The repetition allows for all kinds of allegories to Muses and the multidimensionality of women, but it also amplifies the conformity of the people he paints.

Grey Ribbon (from Alex & Ada portfolio) , 1990

Ada in Black Dress

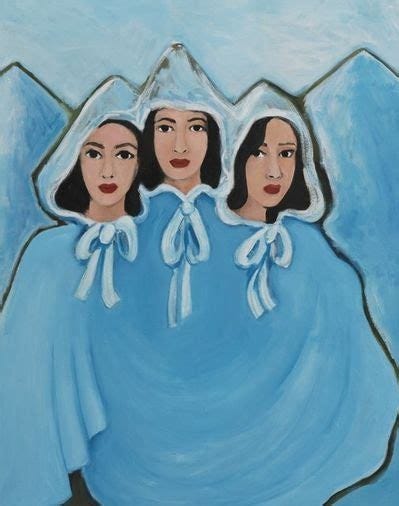

Becky Kolsrud also paints women in multiple, but her figures are less stoic female archetypes and more action-centric heroines in some sort of fable, full of mountain ranges and capes. Her women are engulfed in waves. They stay calm while being overtaken by a natural disaster. They share with all the Adas being well-groomed brunettes, Kolsrud often manicures her subjects’ nails, but these groups of women seem more like the Avengers than a John Cheeveresque gathering of suburban housewives.

Becky Kolsrud, Three Graces, 2018

Becky Kolsrud, Untitled Study (Compression and Fragmentation), 2020

Sometimes Katz gets more expressive and individualized in his portraits. He makes women who feel like women and not icons.

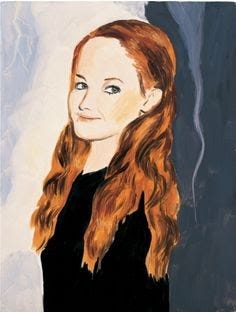

For more of this explore Karen Kilimnik, who uses the same palette as a Medieval tapestry maker, rich blues, auburn locks, dark clothing and porcelain complexions. If Kolsrud is growing super heroes, Kilimnik is painting the cast of Wolf Hall. These are portraits off time travelers, annoyed to be trapped in our era. The women of Kilimnik fit this line from Hillary Mantel:

“At New Year's he had given Anne a present of silver forks with handles of rock crystal. He hopes she will use them to eat with, not to stick in people.”

Karen Kilimnik, The Black Plague, 1995 oil on canvas

Karen Kilimnik, MARY CALLING UP A STORM, 2006

Karen Kilimnik, Little Red Riding Hood Vampire, 2001,

When I look at an Alex Katz group shot the same thought passes through my head as when somebody tries to talk to me about their new cell phone: “I just don’t care.” Never has anybody so nullified the most interesting things of a group dynamic than Mr. Katz. His bland subjects are listless, bored, like all the terrible people in that Whit Stillman movie, “Metropolitan”. Even the details that I think are meant to create some tension in the piece, like a bottle of whiskey in the middle of sedate picnic, do nothing to make me interested in this work.

Alex Katz, Summer Picnic

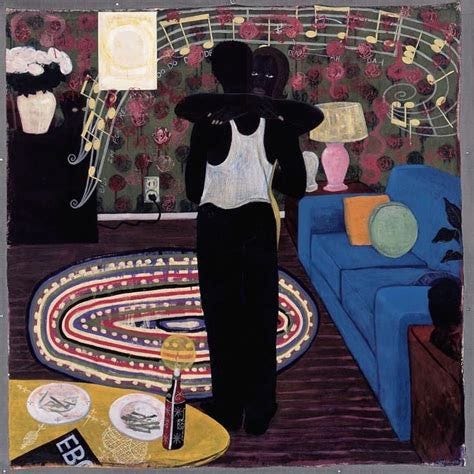

If I gave any of those same scenarios to art world mega-superstar Kerry James Marshall I would get a story I want to hear about because he would fill the canvas with information to pull me in. Young painters should look at Marshall’s work as a master class in adding details, just enough, not too much, and important symbols that don’t take away from the subjects but make them more well-rounded and their lives more palpable. The lives of his subjects are loaded, full of touching and dancing, getting pulled down the street by a dog, and having cocktails, things actual people do.

Kerry James Marshall, Slow Dance

And the way Marshall embeds bold, fluorescent colors as direction signage for the viewer, look here now, then go here - is a master class in establishing the heart of a composition with the careful curation of color.

Kerry James Marshall, Untitled (Dog Walker), 2018.

And if the close up, moody-colored, melancholy of this Ada portrait turns on the new painter, it might be time for them to check out Manet, the original portraitist and also a chronicler of the loners of his own age.

Manet, Alberti’s Window

I’m sure Katz looked at Manet as he was learning. After all, the core of their practice was the same.