There are a lot of similarities in the creative process when it comes to writing and painting. You need inspiration. You need some sort of structure or mission. You must know what criteria defines a great novel and a great painting.

Kurt Vonnegut illustration in “Breakfast of Champions”

And the painter and the writer both face the challenge of figuring out when their work of art is complete.

As somebody who writes and paints, my two sets of ‘Am I finished?’ questions are decidedly different. My writing questions are much more objective and reflect the fact that what determines a successful piece of writing is more well defined. Entire books are given to us on plot structure and the science behind keeping a reader interested and how to make sure every sentence works. My writing questions include: ‘Are my storylines wrapped up?’ ‘Was there growth or change in the protagonist?’ ‘Does my first page hook the reader?’

Making a painting is a much more shadowy process. As a result of that lack of definition, my ‘Am i finished?’ questions are more undefined. And, it is worth noting, they contain the added bonus of being pretty self loathing.

Some of the questions I ask myself as I wrap up a painting include? ‘Is this painting the absolute worst painting ever made?’ ‘Why are the colors so ugly?’ ‘Why does this suck so much?’

The painting above is a current work in progress. I like many aspects of it. The light coming through the trees is great, I like the strong motion of the road leading our eyes into the woods. But my ‘am I finished?’ questions for this (beyond the self-flagellation variety) include, “Is there enough contrast in the colors?”, “Are my marks energetic in the right way or in a messy way?” “Is the brown color of the road super gross?”

Then things get tricky. I do think some of those things need to be resolved, but at this stage in the painting process, there is risk involved in making improvements. Perfecting the color of the road could mean sacrificing the energy in my brushstrokes. Making some lines less messy might negatively impact the quality of others. Painting is all about relationships of color and shape and changing one thing can have a snowball effect on all of the relationships in the painting. Next thing you know, as often happens when I try to trim my own bangs, you have gone too far and ruined everything.

But lucky for us, despite the desire of many artists depicted in popular culture to run around demanding complete creative freedom and abandon and all of that, criteria does exist to help us determine whether a painting is working. Great paintings are great for a reason, they are balanced in form and color, or they are full of dramatic tension in value or subject matter. They make us feel something powerful, or they tell a wonderful story.

So based on that criteria here are some questions to ask yourself:

Question 1: Is there dramatic tension or a pleasing balance? Or, is it lacking tension but also feels unharmonious?

Ask your self if your painting soothes the eyes of the viewer with harmonious colors, like this painting with analogous colors by Monet.

Claude Monet, Water Lilies

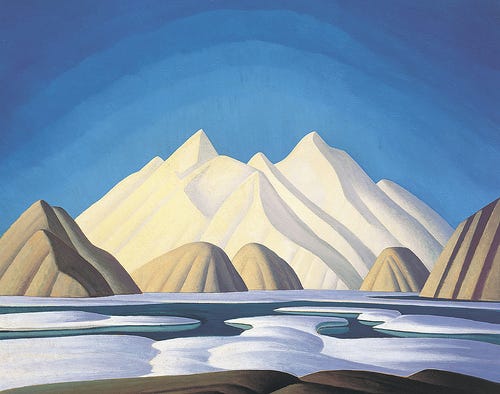

Or examine if your painting has the compositional harmony and symmetry in this painting by Lawren Harris.

Lawren Harris, Baffin Island

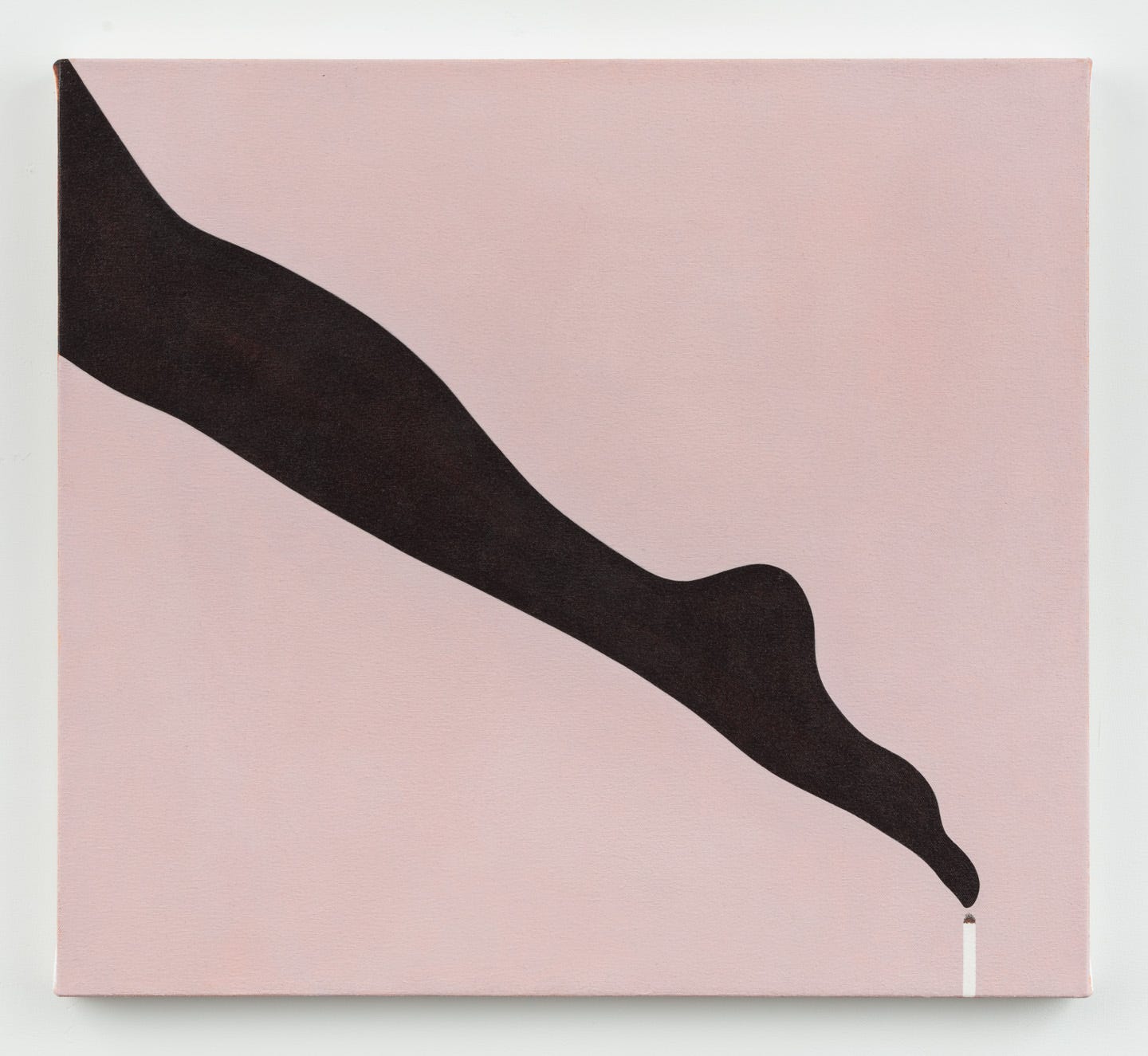

On the flip side, you can ask yourself if you engaged the viewer with a sense of precariousness, like this painting by the contemporary queen of tension, Alice Tippit.

Alice Tippit, Secret, 2017

And could there be anything more dramatic or full of tension that makes us want to spend time with a work of art than Raphael’s depiction of Archangel Michael’s hand-to-hand combat with the demons of Hell?

Raphael, St. Michael

Question 2: What is the weakest part of this painting?

The most important part of your painting process is looking at your painting. Most artists spend 90% of their time just looking at the marks they have made so far. All of that looking and staring should begin to reveal to you where you eyes keep returning. Usually our eyes are drawn to a spot on a painting because it is either so awesome that you can’t look away, or whatever is happening there is not working. And if that area is not working, ask yourself why not.

Consider if the colors are too muddy, the composition is too chaotic or too boring, or maybe your marks lack energy. Try again in that spot with a more dynamic color or bring it to life by inserting an object in it, a patch of wildflowers or a dark shadow. Or have a couple of espressos and make three brave marks in a very brave color.

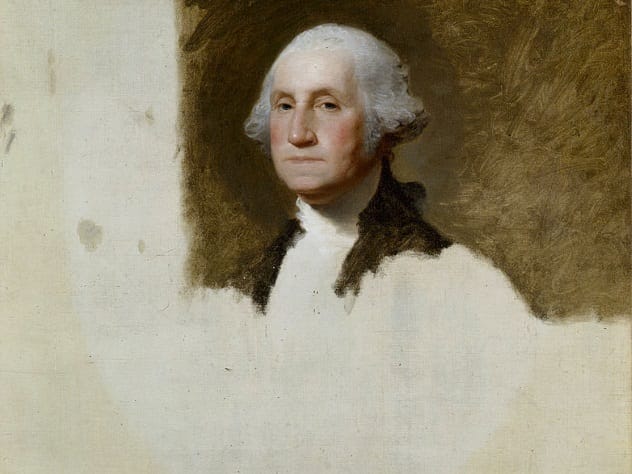

Gilbert Stuart’s Unfinished George Washington painting

Question 3: Does everything seem intentional?

This is something I talk to my students about a lot. New painters often get to a stage where they love their painting and want to quit, reasonably afraid that their next mark will be the one that will ruins their efforts. But this often means too many things are left unaddressed and so the work feels unintentional.

I might gently prod them with questions about the bits of exposed canvas that remain. “Is it on purpose that there is no paint on this area?” I ask. They will often admit that the canvas is exposed because they were unsure about how to paint those areas or because they didn’t know what color to use.

The opposite artistic move made by new painters is to randomly cover the canvas with a color in an effort to kind of just be done with it.

Jackson Pollock, Number 8 (detail)

I almost think the kind of thoughtless covering of space is better than a thoughtless lack of coverage, but these are opposite ends of the same problem: a lack of intentionality. The space in the world you are creating goes top to bottom, edge to edge. Your marks have to reflect that you see every square inch of that canvas as important.

Question 4: Am I moving the eye around the canvas?

If you intend to give us a representational world in your painting, with a foreground, middle ground and background, have you given us the depth required to move us through space?

The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere, Grant Wood

In this Grant Wood painting he has manipulated value, perspective and motion to have us move along the road with Paul Revere as he races to warn of the advancing British troops.

If you are creating an abstract piece, are you using color and shape to direct the eye around the space?

Joan Mitchell, Slate

In this Joan Mitchell piece her strong, dark lines have us traveling in a wild motion around in circles. But in the piece below, her mastery of her marks have us delightfully settled into a collapsed middle of the painting.

Joan Mitchell, Reverie

It doesn’t matter how long you have been painting, one month or multiple decades, knowing when a painting is finished is one of the biggest challenges of painting.

But by being thoughtful and objective in that final stretch, and by asking yourself the right questions, you should be able to determine when a piece is ready to leave your studio.

Find more hot tips in my book, Painting Can Save Your Life: How and Why We Paint.

Happy Painting!

Sara

Not just interesting, but beautiful to look at!