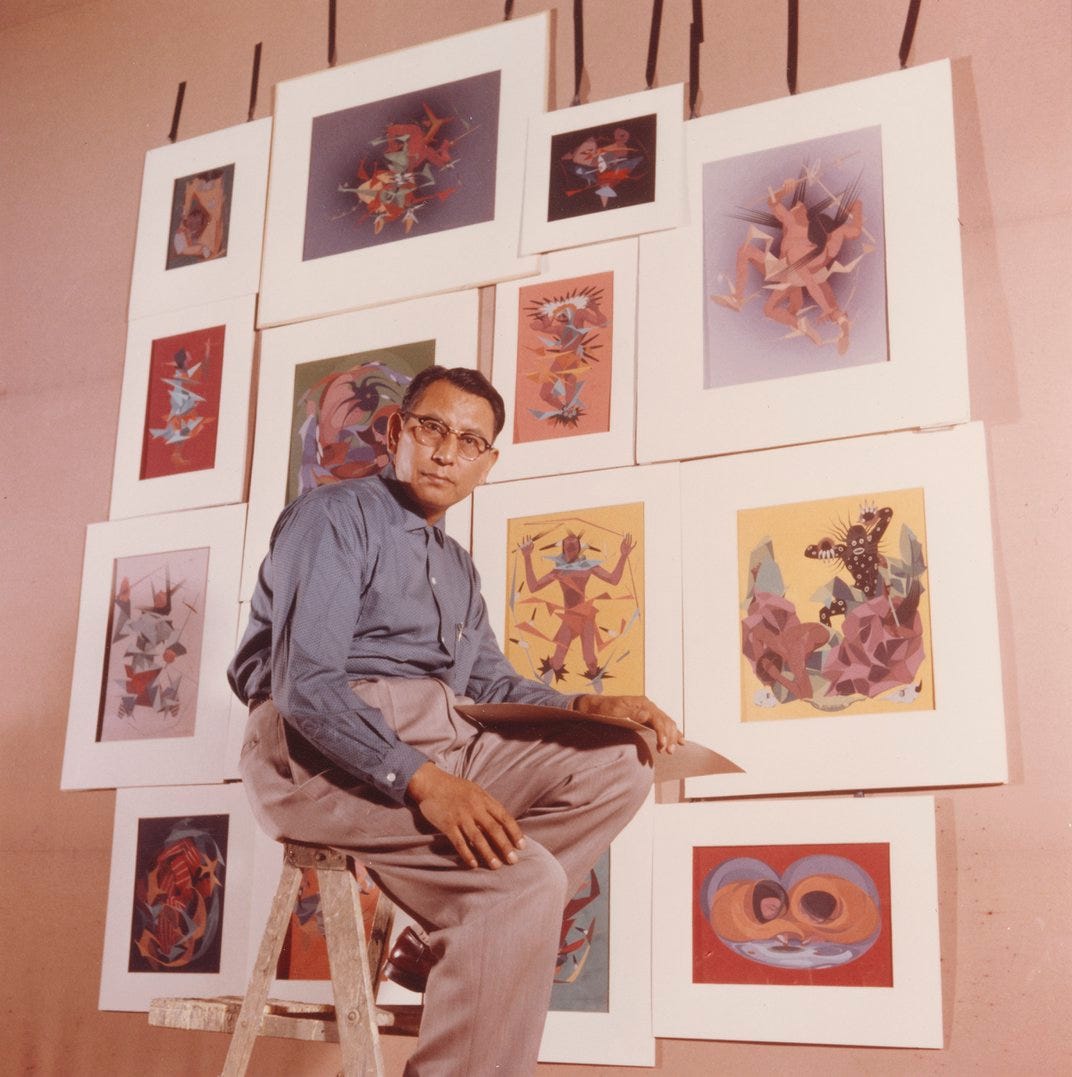

Painter Oscar Howe is having a moment with a long-overdue retrospective, Dakota Modern: The Art of Oscar Howe, which I had the pleasure of seeing at the National Museum of the American Indian in New York, and that will soon open at The South Dakota Art Museum in my lovely home state.

Unless you also grew up in South Dakota and were taught about his work from an early age (there is so much pride in Howe that an elementary school in Sioux Falls is named after him), there is a solid chance that you do not know about this important American painter.

Howe had a few strikes against him in terms of reaching the level of global fame that a painter of his skill and innovation should have reached. He was not a white, Ivy League educated or coastal elite. He was Yanktonai Dakota, born in the Crow Creek Reservation in South Dakota, and he got his undergrad degree at Dakota Wesleyan University and his MFA at University of Oklahoma.

Oscar Howe, Dakota Medicine Man, 1968

I can’t write a better broad overview of this artist than this text from the NMAI and this piece sharing Howe’s own words about his place in art history and what Native American Art should look like. “Who ever said, that my paintings are not in the traditional Indian style, has poor knowledge of Indian art indeed. There is much more to Indian Art, than pretty, stylized pictures,” he wrote in a letter.

And on the important of his Native American culture on Howe’s work this article from American Indian Magazine says, “Howe’s work does not go against tradition but expands the way those traditions can be expressed. Though grounded in culture, his experimentation and rejection of realism places him squarely as a modernist.”

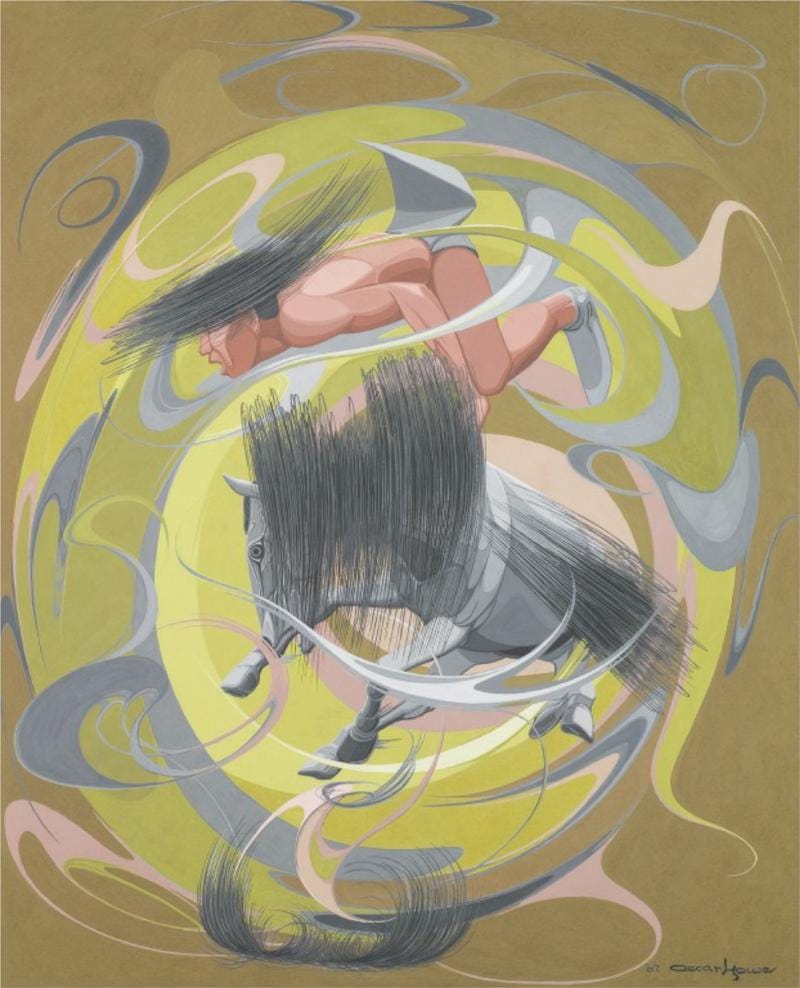

Oscar Howe, Breaking a Wild Horse

My painting students recently looked at Howe in terms of the movement he brought to his paintings. His brush marks captured the energy of a person or an animal in motion, and in doing so Howe breaks up the plane of the painting in a singular, exciting and ground breaking way.

Oscar Howe, Sacro-Wi-Dance, (Sun Dance) 1965

Howe disrupts the space so much that all of us viewers are left feeling unsettled and wondering where we are in this world. Are we looking down from an aerial POV or standing in front of that bucking horse? Is the dancer whirling around me where I stand or swirling up into outer space away from me?

His marks and shapes represent the atmosphere of the world around the subjects in a somewhat surrealist spirit, but the shapes becomes so simplified that he is almost an abstract painter or a Precisionist painter like Georgia O’Keeffe or Charles Sheeler.

Charles Sheeler, Pertaining to Yachts and Yachting, 1922

Georgia O’Keeffe, Red and Orange Streak, 1919

Some have tried to label him a cubist like Braque or Picasso because of how he breaks up his world into geometric shapes, but those cubists were trying to flatten the world. Howe’s world leaps from the page at us, as if whatever dimension we are in is being shattered and the chunks of our world have broken free of the canvas and are flying out of the page.

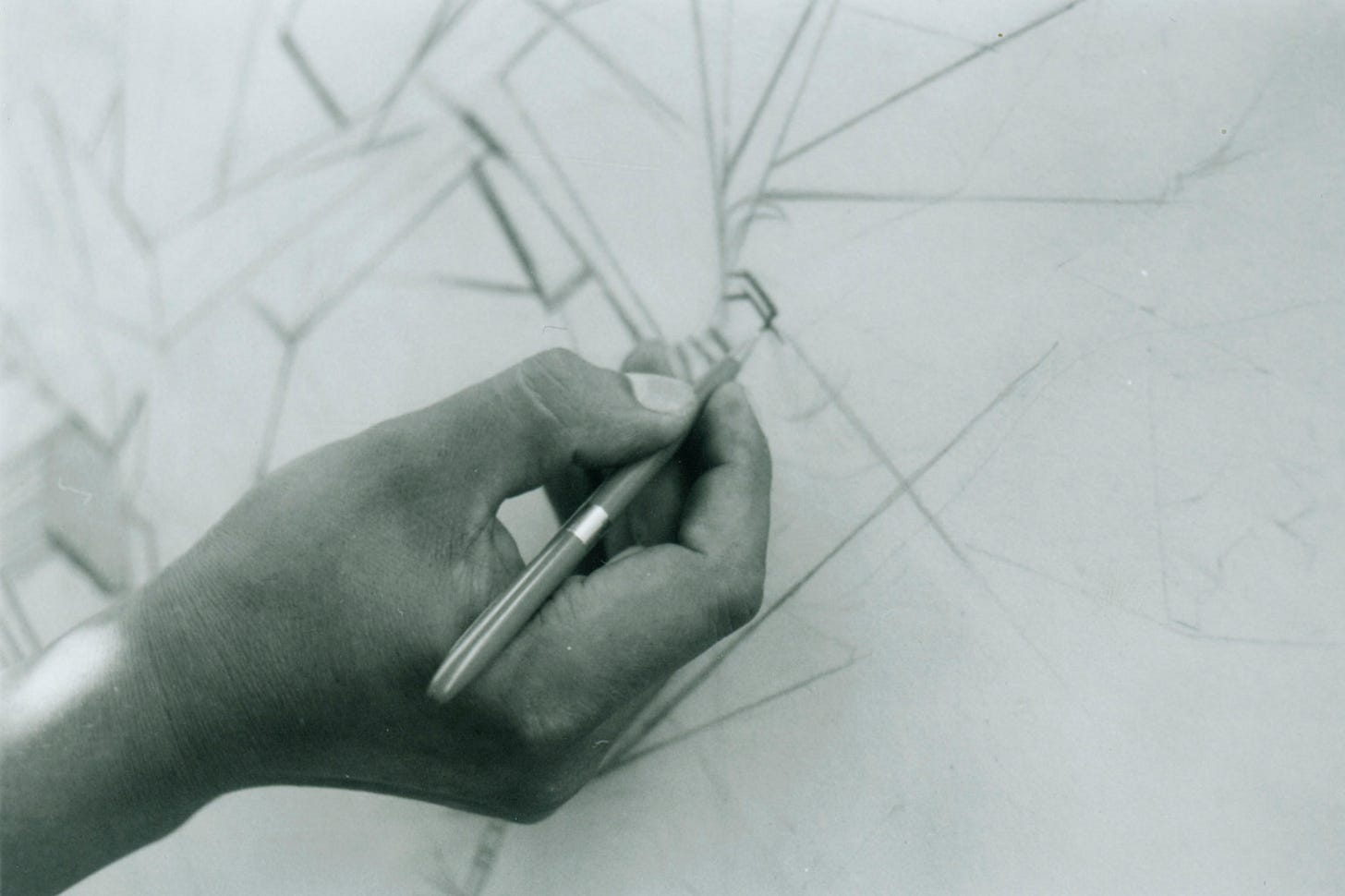

This University of South Dakota Archives and Special Collection connects this aspect of Howe’s work to a “geometrical point-and-line compositional device that he (Howe) referred to as tahokmu, or the ‘spiderweb,’ in which designs are generated by a web-like network of points…Howe explained that traditional designs were ‘diamond shaped with one deer hoof track design at each end, that is left and right horizontally symmetrical. From this design comes all geometric designs…'” (Anthes 166).”

Oscar Howe works on piece, 1960 - from Universities Libraries, University of South Dakota

In his 2022 New Yorker piece on the Oscar Howe, Peter Schjedahl wrote “The vertiginous composition incorporates tropes of Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism, which, having become second nature to Howe, hardly vitiate the intensity of this particular religious rapture.”

Let me give you a little relevant art history context here: Any time an artist has everybody scrambling for some art world comparison or art movement to cling to, that artist has come at us with something entirely new. And innovation in painting is a very, very difficult thing to do.

Of course the movement and motion doesn’t exist for movements’ sake, yes the gestures and marks add to the story of the bucking horse and sun dancer, but it also creates an emotional response in the viewer of anxiety, excitement, or even that rapture Schjedahl referred to.

And it is worth noting that at the end of the day motion and movement in art is generally pretty emotional because it is showing that we are not staying here forever, that every time a wave moves towards a beach it will result in change, each time the sun rises and sets it is a reminder that there was a day before this that is now gone. I know, what a bummer.

What other artists excel at using movement and motion to bring the viewer to a place of rapture or grief or breathlessness?

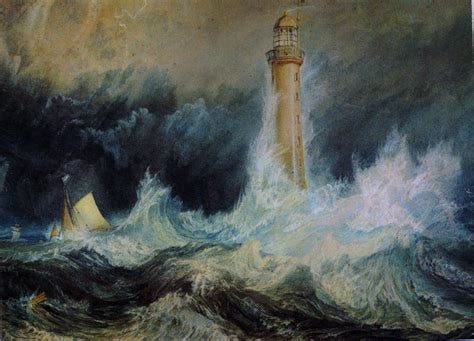

JMW Turner, The Bellrock Lighthouse

Turner and his wild, heart-stopping waves, crashing and taking lives, so full of intense motion that we can almost hear their attack on the lighthouse.

Dana Schutz, Building the Boat While Sailing (2012)

Schutz often gives us a world of movement resulting from mayhem, leaving the viewer unsettled and anxious.

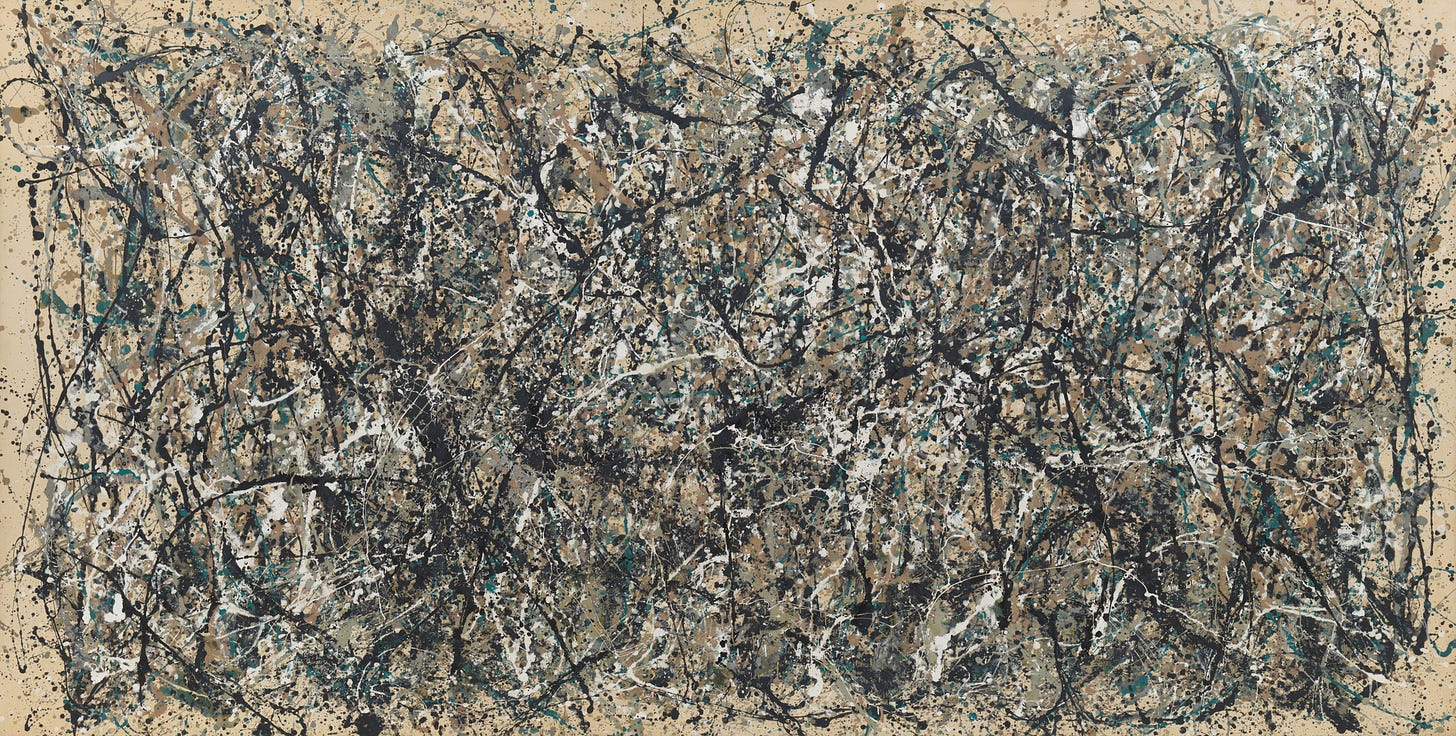

Jackson Pollock. One: Number 31, 1950. 1950

Nothing but motion in this, thanks to the endless movement of the artist, the viewer is taken through a joyous circuitry of marks and drops.

GLADYS MGUDLANDLU, Birds Over a Field, 1962

Mgudlandlu is like Howe in how she plays with perspective, often painting from above like the birds that are often flying across the page and bringing our eyes with them, resulting in an emotional state of excitement.

Tala Madani, The Ascendant, 2018

Madani’s canvases are full of motion, often of a kind of grotesque variety like urine or neon-colored vomit flying across the page, leaving the viewer amused and kind of grossed out by humanity.

Edvard Munch , The Sun, 1910-11

Munch used movement of his objects and skies and sunbeams to double down on whatever emotion he was handing us, whether that is tragedy or joy.

WHO NEEDS A MUSE? PAINTING EXERCISES.

Spend time looking at Oscar Howe’s work and then find an image you would like to attempt in that style. Find something in motion. Maybe your child flying into the air on a swing, your dog pulling you on a leash, a bird in flight. Break it down in pencil first, trying to use as many geometric shapes and swirls as you can. Keep your palette subdued or similar, and try to make all of the tension happen with the movement of the shapes.

Paint a pastoral landscape with motion and movement in mind, a la Munch. Try to overwhelm your viewer with the energy of your marks as you drag them here and there through your sky and your ocean. Your waves should jump off the page, the moonbeams burst into the eyes of the viewer. Drink a couple of Red Bulls before you start.

Paint a sky full of birds a la Mgudlandlu, with the birds pulling us across the page.

Thank you for reading! If you like this newsletter please check out my book for more o the same… “Painting Can Save Your Life: How and Why We Paint”.

Happy Painting!

Sara